Running as fast as I could I soon realized that it was a race between me and them. ‘Them’ were the platoons of German, Polish, Ukrainian, Lithuanian, and some Jewish police, who had liquidated the neighboring townships of Tarlow, Ostrowiec, and Opatow, and were now moving into Ozerow. The noise of motor vehicles filled the air and a multitude of flashlights and flares lit up the alleys and passageways on this cloudy morning of Sunday October 25, 1942. The forces of the Reich, perhaps hundreds of men, werein the process of making the world Judenrein. Ozerow was being cordoned off from the surrounding fields to make sure that no one could escape the trap. Long practice in dozens of Shtetlach made it easy to form a police cordon to seal off the Jewish towns from the neighboring villages. Would they get me too?

Only some 100 meters separated our dwelling from the open fields towards the east. As I ran I passed two cottages. The first belonged to Reb Rivele, Ozerow’s Rav and Rabbi, the saintly miracle man who was famous before the war for reputedly being able to exorcise dibbukim, ghosts who loved to visit the bodies of unfortunate maidens. Behind this house was the barn and cottage of the Wojtockis (Voytozkis), the peasants from whom I used to buy milk. The Rebbe’s dwelling, where I used to spend many days as a youngster, now seemed absolutely still on the this dark morning. But the barn of the Wojtockis was a hub of activity. Having passed no more than 20 feet beyond the barn I heard shouting in Polish: “halt! halt or I will shoot!” Ignoring the shouts I doubled my efforts to run even faster and faster. When shots began to trail me I squatted, crawling on all fours. I must have crawled for a long time, for when I got up to take a glance backward, I could see nothing but a deep mist that enveloped the houses. The cottage and barn of the Wojtockis were no longer visible.

The deep, dark mist that covered the morning light also enveloped Ozerow. It might have been assumed that the shtetl ceased to exist. But the swishing sound of bullets fired from a variety of guns told eloquently what was happening in Ozerow. Whom did these shots murder? Not my older sister Hendele, already slain by the bullet of the conquering cyclist. Were they killing the remainder of my family—my brother Aaron and sister Shifrah? The Germans enjoyed themselves by shooting characters like my father, with his broad forehead, thick eyeglasses, unkempt blondish beard, who was in addition lame. Such Jews were anathema to the Christians, even ones who were not members of the Nazi party. My father presented them with a figure of the Old Testament who must be uprooted. I knew that my father’s chances of surviving the collection of the people into the market was nearly nil. As the shooting continued I wondered which of the shots penetrated his body.

I wondered about the fate of the two cottages that I passed by while running away. Calling one of these houses Reb Rivele’s is a misnomer, since Rabbi Reuben Halevi Epstein had died in early 1940 and the house was now inhabited by his children, his son Rebbie Yehiel and daughter Hannah. As far as the people of Ozerow were concerned, however, Rebbi Rivele was still among the living. If he had died before September of 1939 there would have been a massive levayah, in which every inhabitant of Ozerow would participated, even the town’s most outspoken apikorsim (of which there were many) and Jews from neighboring towns. When he died on Hol Hamoed Sukkot his son Rebbi Yehiel succeeded him, but no one knew the difference. But I did. Even as a child I loved to frequent this house where more often then not the servant would give a half fresh roll with a thick layer of butter which to me seemed the height of good living.

Rebbe Rivele’s deeply melodious chant of his recitation of the Zohar revealed to me the mysteries of the universe and the three souls that reside within every being, even the beasts of the field. When he intoned the mysteries of the Zohar during Shalosh Seudot, the heavens opened and the angels joined in the chanting, although as was well known, angels are handicapped since they have never mastered the Aramaic language.

Years later, when I had become an apikores, my thoughts continued to linger in Reb Rivele’s house. His son Rebbe Yehiel was a sharp contrast to his father. Rebbi Rivele’s face looked as if it was illumined by the sun of the Gan Eden. Although the Book of the Holy Zohar was always kept open in front of him, Reb Rivele’s blue eyes frequently turned towards the window panes, with his wife the Rebitzin often hurling charges that he was watching the female passers by.

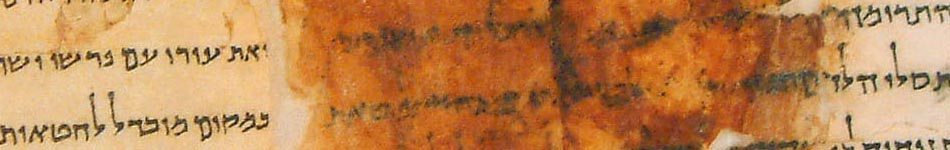

Rebbi Yehiel’s face had none of the “hadrat panim” of his father. His pale face with its grey eyes and his whole body was stooped towards the print in the oversized large folios. Unlike his father, whose entire shelf of books was limited to of Tikkunim, Zohar and a mass of booklets which told miracle stories performed by the Hasidic Rebbes, Reb Yehiel had a study that consisted of two rooms. All the walls of both of these rooms were filled with the folios of Talmud, the Vilna Shas and Poskim, commentaries, super-commentaries, and super-super-commentaries.

Ozerow had quite a few libraries. In the Beit Hamidrash tomes of the Talmud and the like could be found, but the sefarim were uncared for. The various youth organizations housed Yiddish books, including various classics, such as Dostoievski and Tolstoy, along with the trashy novels that flooded Western Europe. The Bundists and the Communists possessed large quantities of volumes that dealt with dialectical materialism and other Marxist literature. But only Rebbe Yehiel had a whole library to himself. Walls and “shanks” of sefarim that dealt with the minutiae of the Halakah. So, while Rebbi Yehiel was never my favorite, his library was. We used to sit on opposite sides of the large pine table and without acknowledging each other’s presence.

I soon noticed that while I would sit and peruse the tomes in Reb Yehiel’s library his sister Hanaleh, whose face resembled her father’s, with large brown eyes, would find an excuse for being in the adjoining room. The two of us played when we were two years old. Now we merely exchanged glances when we passed each other. Each of us was too timid and inarticulate to even hint that we were deeply attracted to each other.

For a moment as I glanced for the last time at the Hurban of Ozerow the thought of Hanaleh and Rebbie Yehiel lingered in my mind. What will happen to the hundreds and hundreds of sefarim, those huge tomes that covered the walls and filled the closets? What will happen to the house where I could always find refuge from the prosaic world and enter into a world of mysticism and rabbinic scholarship?