(1) Notes From a Granddaughter, by Tzipora Wacholder

(2) Sholom Wacholder’s talk at Ben Zion Wacholder’s Memorial Service in New York

(3) Hannah Katsman’s eulogy for her father Ben Zion Wacholder

Notes From a Granddaughter

By Tzipora Wacholder

My Zaidy:

You were a wonderful grandfather. You did so much for all of us and showered us with love and attention. You cared that we should think and learn and grow. You exemplified the phrase “lifelong learner” and were able to communicate that to all of your descendants.

I was happy to have introduced myself to you one last time. The conversation we had, each time I came to visit, replays in my head. Zaidy would grasp my hands firmly, and ask “Who is this?” I would say “This is Tzipora. David’s daughter.” You would call me your lovely granddaughter and tell me how much you love me.

Whenever we saw you, we would cuddle next to you and talk about our lives. Zaidy was always most eager to hear about our studies. “Do you like school?” he would ask, “What are you learning?” Then he would ask us incisive questions in order to deepen our understanding.

Occasionally he would teach us an interesting random fact. I remember him telling me about the beauty of prime numbers, and his delight in how many of the special numbers in Judaism are prime, such as 613, 13, and 7. He loved all kinds of knowledge and, even more, he loved sharing his knowledge with others. His enthusiasm was contagious.

Zaidy treated every person with tremendous respect. He did not discriminate between people by status, money, religion, or even age. Anyone he met was judged solely by their content. This enabled him to speak as easily to a child as to prominent academics.

Zaidy related to each person on their own level, but he especially loved children. My earliest memory of Zaidy is him playing with my fingers, trying to find the one that he claimed had “disappeared”. “Hmmm, this is interesting”, he exclaimed, “You only have 9 fingers!” His talking watch was another source of endless fascination to us children.

As a grandfather, Zaidy was very loving. He would feel our faces and tell us that he has beautiful grandchildren. Although he never saw our faces, it was uncanny how he could follow our thoughts.

My siblings and I spent several Shabbosim with Zaidy in Aunt Nina’s house. Zaidy was fun to spend Shabbos with because he so enjoyed participating in everything. We would sing Zmiros with him. Everything he did was done in a complete way. When he sang with us, it was with his entire heart and soul. Although he did not have a melodious voice, he more than made up for it with his enthusiasm and joyous smile. Even when he didn’t have the strength to sing, he would bang on the table.

Zaidy always encouraged our learning. To him, it was like breathing. We knew to be prepared for a grilling about anything we mentioned learning in school. In both secular and religious topics, Zaidy could test us and teach us something we hadn’t known. In Jewish studies, we knew that with a prompt of only a few words, he could — and would — recite most things from memory, and that included the Bible, the Talmud, and commentaries.

Zaidy respected every point of view, as long as it was logically consistent. I remember an incident that occurred while I was reading to him a book he had authored. He suddenly stopped me and asked what my opinion was on what he wrote. Knowing the high value he placed on intellectual honesty, I answered “I think it borders on the heretical.” He very much enjoyed that.

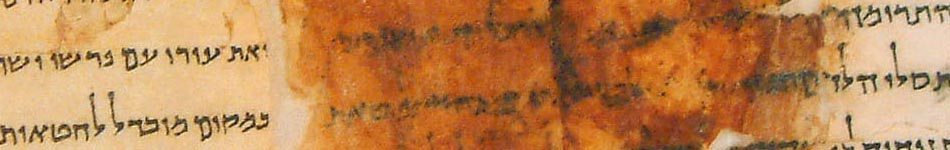

He was an extremely honest person with strong principles. He believed that knowledge cannot be hidden and should be in the public domain. Although he possessed a very easygoing personality, he did not hesitate to stand up for his principles, as in the matter of publishing the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Zaidy was a Holocaust survivor. With his talent for languages, he was able to pass himself off as a gentile laborer. Although we asked, he did not share much about those frightening times with his young grandchildren. Instead, he told us the humorous story of how he passed time teaching “Gemoorah” to the cows while working in a farm. “Ge-MOOOOO-rah”, he emphasized, with that special twinkle.

Education was so important to him. He came to America in his late teens, and earned a doctorate degree. When I was in high school, he would always ask me, “Are you in college yet?” When I reached that point, he was no longer able to converse in depth about each course, but he immediately wanted to know what I was going to study for a doctorate degree. He was so happy whenever he heard that someone was pursuing higher education. To Zaidy, learning was everything in life.

Although he lacked sight, he possessed the sharpest insight. He sensed when someone was not being completely honest with him. Zaidy only wanted to hear the truth. Maimonides says, “Accept the truth from wherever it comes” and Zaidy excelled in this. Consequently, he loved critiques of his work and sought them out.

Zaidy was a proud Jew and a true “Person of the Book.” He authored many books and articles during his life and wanted the last book he published to be an autobiography.

Every visit involved a lot of reading. He never tired of it — instead, the more he learned, the more he wanted to learn. More recently, we would read him the last book he published, The New Damascus Documents: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Reconstruction, Translation, and Commentary. He was very proud of this book. He most loved hearing our questions about his work. Whether explaining “eschatological” to a 12 year old or debating a Talmudic point, Zaidy would go to great lengths to make sure he was understood.

For as long as he physically could, Zaidy insisted on going to shul to pray. This involved a long and tiring walk, but he loved the atmosphere in the synagogue.

Zaidy loved all of his grandchildren deeply. He expressed this love through loving words and actions, but most importantly by instilling a love of learning and thinking. Each grandchild perceived Zaidy in a different way. Zaidy was like that. He spoke many languages and was a polymath. No one could compete with him in depth or breadth of knowledge, so he would discuss whatever interested us. In this way, he made us feel comfortable with him and was able to teach us as only he could. I know I have only merited to glimpse a few aspects of the complex person who was my grandfather.

It would make him happy to know his children are going to Israel together with him, and that his grandchildren remember his example and his accomplishments, and value his legacy. And yes, Zaidy, we are going to read your book.

Sholom Wacholder’s talk at Ben Zion Wacholder’s Memorial Service in New York

As I sat on the train this morning preparing, and debating whether I should speak with the help of a computer, I looked to my father’s example for answers. And I decided, Whenever you have something to say, the key is to express yourself well within your capabilities: don’t worry about convention and don’t worry about everything you do not know when the goal is to achieve an important end.

In recent years I have heard many mourners tell stories about a beloved person who has died. But funny stories or camping trips or sports events did not come to mind as I remember my father these past few days. Instead, I want to share one dominant aspect of his person and of his personality.

My father knew all 613 mizvot, but he profoundly personified one of them. He would have been happy to observe the mitzva “v’shinantam l’vanecha” – Teach them [teach God’s words] to your sons— every waking hour of every day.

He had expansive views of these words. To him, God’s words encompassed all the texts he studied so joyfullly: the Torah, and the Talmud, and the Midrash, and the Rishonim, and the Acharonim, and contemporary she’elot and Responsa and academic Judaica scholarship too. And God’s word encompasses science and history and philosophy and math.

To Daddy, “Teach these words to your sons” has an expansive definition of “sons.” Not just David and me, but Nina and Hannah, and 15 grandchildren, and in-laws too. His sons included every student he had in a class, or anyone who would listen to him and respond. Young or old. Male or female. Jew or non-Jew. Just ask the aides who took care of him for these past few years.

To my father, teaching encompassed learning. He learned so he could teach. He taught so he could learn more and teach better. His life was not balanced. He was obsessed. His obsession was not food, or art, or music, or movies or sports. His obsession was “torah lishma.” Torah for its own sake. He always wanted to understand my work, about as distant from the focus of his own study as possible, and see whether it would help him learn and teach. And he created disciples who follow his example: As I made phone calls yesterday, I heard at least twice, once from a rabbi, once from a Christian scholar: “Ben Zion changed my life.” He changed many lives: not just those he knew intimately, my mother, my sisters and brothers, but everyone he knew. That is what teaching by doing accomplishes.

Over the past years of slow cognitive decline, my father developed a tic. Almost at random, he would ask “Have you read my book?” Many times a day. Sometimes once a minute. I see this tic as an expression of his frustration at not being able to learn and teach at a high level. He was begging for us to engage with him in his work to force him to learn more deeply so he could teach more fully and more effectively. He was really saying: “I want to hear your thoughts about my work: Your questions, your challenges to my interpretation. I want you to teach me something new so I can learn more and teach something new about the Damascus Document.”

My father’s example of living the holiness of Torah lishma is his most profound teaching. When our own lives transmit his love of Torah, lilmod u’lelamed, to our own children, our students, our mentorees, our friends and acquaintances, we are simultaneously honoring Daddy’s memory and fulfilling the mitzva of “Ve’shinantam levanecha.” And as those who learn from us teach or grandchildren and grandmentorees, we preserve and perpetuate an ancient tradition in infinite progression, and honor ancestors who created the tradition; direct ancestors, and ancestors who are unrelated to us genetically; ancestors whose names we remember and ancestors whose names we do not know.

Hannah Katsman’s eulogy for her father Ben Zion Wacholder

Once, when I was about ten, I repeated to my father something I had heard or read somewhere: That the only two English words in the English language with no rhyme are “orange” and “silver.” A couple of hours later, when he happened to pass me in the hall, he said only one word. “Chilver.” “Chilver’s not a word,” I challenged him. “Look it up,” he said. At that stage in his life, he couldn’t see well enough to read. So I went up to his study, where he kept an unabridged dictionary open on top of the file cabinet. Sure enough, chilver was listed. For the record, it means a female lamb.

This was typical of my father’s approach. He never took anything for granted. When he heard a statement of fact, he immediately questioned it. He enjoyed the intellectual challenge of examining facts and looking at a question from various angles. Maybe there is something that rhymes with silver. He didn’t argue to demean others or to prove he was right. He just wanted to find out the truth.

Several years later I mentioned the incident to my father, how I was impressed that he knew the word chilver. He admitted that he hadn’t actually known whether or not chilver was a word. He was making a guess, which he wanted me to confirm as true or false.

John Kampen and John C. Reeves, students who edited the festschrift in honor of my father’s 70th birthday, wrote: “All of us remember occasions when the results of his most recent research contradicted his own earlier conclusions. “So I was wrong!” was a frequent response to queries about his own earlier judgments.”

When my father’s theories were attacked by colleagues in the academic world, he never took it personally. In fact, he relished the attacks because they gave him a chance to return to the texts and find something he might have missed. He loved to learn things that shed light on a question. It didn’t matter whether or not the information ultimately supported his position.

For his children, students and colleagues he was a model of authentic scholarship. As a child I was amazed by his complete dedication to his work, often until the early hours of the morning. You would find him in his armchair near his typewriter. Occasionally he would be reading with the help of a magnifying machine—he needed the highest level of magnification, which allowed him to read only one or two words at a time. My bedroom was on the same floor as his study, and I can still hear the ping that signaled the end of the line on the manual typewriter. When you reread his work, though, many of the lines still went off the page. Typing without sight, he spelled out his thoughts that he later reviewed with his students. With the advent of new technology, he progressed from a manual typewriter to an electric one, then an electronic one, and finally to one of the earliest computers that read text aloud. Of course, few of the basic Jewish texts were digitalized at the time, much less the obscure ones he specialized in.

But mostly he sat in his study for long hours, just thinking.

Whenever I stopped by the study, whether to call him to dinner or relay a message from my mother who rarely climbed the stairs, he invariably asked me to look up a few of the sources he was working on. He would say, “Take out Josephus,” or the Book of Jubilees, or Encyclopedia Judaica, or the Gemara. The walls of his study were lined with books—my mother refused to allow bookcases in the living room—with many more piled on the floor. My father would direct me to the correct shelf and help me locate the page—he knew every one of his books intimately.

During high school my father summoned me to spend hours in his study, mostly reading Yigeal Yadin’s new commentary on the Temple Scroll of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which fascinated him. In recent years, he would be happy with an offer to read any text, although he preferred to hear his own newly published book on the Damascus Document. One when I was reading it to him, he remarked, “You read very well.” I had a lot of practice.

Officially his field was Talmud and Rabbinics, and he taught the Talmud, Shulhan Aruch and other texts to Reform rabbinic students. My father enjoyed teaching beginners as well as the series of advanced doctoral students who spent several days a week at our house, studying with him both in their own fields and whatever my father was researching at the time. My mother served them lunch and they became part of the family. A couple of years ago one came to visit me here in Israel while leading a Christian group from the Philippines.

When I told one of my friends about my father’s death, she pointed out that my father lived the life he wanted to live. He got paid to teach, write, and mainly to think about the things that interested him.

It wasn’t always easy being the daughter of a welll-known Jewish scholar. Once, a friend talked me into accompanying her to ask our public school teacher to give us an extra few days to study for a test, claiming that we needed the extra time because we had to prepare for the upcoming Passover holiday. The teacher, who wasn’t Jewish, looked at me closely. “Hannah,” she said, “Does your father know about this? The teacher was right, of course, as my father didn’t know and wouldn’t have approved.

My father was also well-known around the neighborhood for his long daily jogs in all weather. Occasionally he got lost or injured, and a stranger, or sometimes a policeman, would bring him home. My mother once insisted that he tell her his usual route so we could locate him if he failed to return. When his picture appeared in the paper because of his work on the Dead Sea Scrolls, we learned about the many friends of all ages he had acquired on his walks. They saw him as a blind, eccentric and very friendly fellow, and were shocked to learn of his international reputation.

I visited him every summer in recent years, taking along a few of my children for him to enjoy. It was sad to see him decline, yet we also saw a flowering of affection toward his children and grandchildren.

[At this point Hannah read the eulogy written by Tzipora Wacholder.]

We invite you to share your own memories Ben Zion Wacholder by sending them to BZWacholderMemories[at]gmail[dot]com.